Provenance:

European Private Collection, acquired in 1993

Published:

Jane Casey, Taklung Painting: A Study in Chronology, Serindia Publications, 2 volumes. 2023: vol. 1: 233-235, catalogue 15

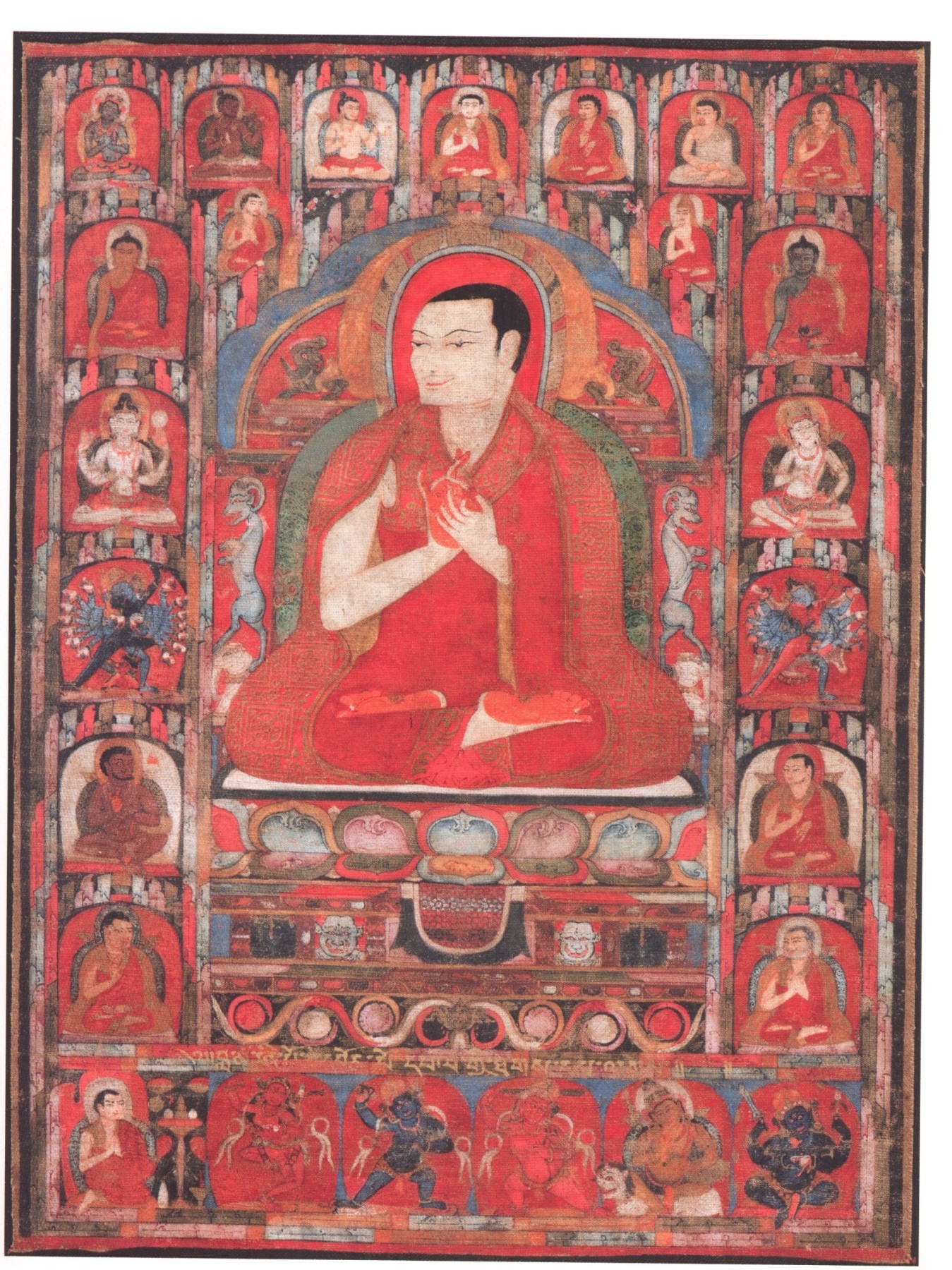

The present thangka is understood to represent an Abbot of the Taklung monastery with an entourage of his spiritual ancestors and his protective deities. He is represented as a young man, enthroned, within the rainbow arches indicative of his attainment of "the rainbow body," a sign of great spiritual mastery.

This refers to a phenomenon seen by the devout students upon the death of their teacher, where the image of the teacher is surrounded by a rainbow. This is most often found in thangkas painted in homage to the teacher’s memory, possibly at the time of the one-year celebration after a lama’s death. Occasionally, however, exceptional teachers are believed to be capable of manifesting the rainbow body to their disciples during their lifetime. Here the Taklung Abbot is seated in the lotus position with his right hand forming the dharmacakra mudra of teaching, gently holding his hands over his heart. Above his throne, in the left corner, is a Tibetan monk with a goatee, and at right, an Indian teacher sporting a moustache, recognizable by his gold pointed hat, and wearing a red robe.

In the upper register the lineage stems from deep-blue Buddha Vajradhara, who is seated holding the vajra and bell which symbolize the union of indestructible strength and wisdom of the Buddha's teachings. Vajradhara is accompanied by five aspects of the meditation deity Guhyasamaja-Manjuvajra, in female form, as indicated by the short blouse worn over her shoulders and upper chest; the five are represented in five different colors, as an analogy to the Buddhas of the Five Families (Vairocana, Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha, and Amoghasiddhi) and their dominion over the five directions (center and cardinal points) of the world At the center of the upper register, immediately above the Abbot’s head and nimbus, is the portrait of a Tibetan monk whose head is turned in reverence towards Vajradhara. He has a slight goatee, he smiles gently with lips closed, and his hands perform the dharmacakra mudra of teaching.[i]

A series of Buddhist teachers are represented along the left border of the thangka. Immediately beneath Vajradhara the mahasiddha Tilopa is seated, followed by the mahasiddha Naropa, shown holding a skullcup. Naropa's famous student was the Tibetan translator Marpa, who is represented here with neck-length black hair and wearing an elaborate gold brocade cape and red robe with wide belt at the waist as befitting his status as a layman not a monk. Marpa's student was the ascetic Milarepa, here dressed in white robes and holding his hands in dharmacakra mudra over his heart. This early iconography for Milarepa is found principally in thangka paintings of the 13th to early 14th century.[ii] Below Milarepa are two monks, which, if the historical progression is respected, should be portraits of Gampopa and his illustrious disciple, Phagmodrupa, seated at the level of the lotus petals of the hierarch's throne. A white Vajrasattva is seated beside the lion and elephant throne supports.

The lower register of the thangka shows, at far left, a seated monk in devotion. He is performing a consecration ritual, with several offerings in golden bowls, and, above a pedestal with crossed fly-whisks, the red volume of the Prajnaparamita sutra lies beneath a golden stupa. There are six seated deities, the female deities each wearing a diadem with three golden triangles while the male deities have a tiered crown with high chignon adorned with a gold finial. The first goddess is a brown aspect of Tara (?), holding the stem of a lotus in her left hand and with the right hand in the varada mudra of generosity and boon bestowing. White Avalokitesvara is seated beside her, holding the stem of the lotus and both hands over his heart, and a blue aspect of Vajrasattva holds a bell in his left hand and a double-vajra over his heart. A red Tara holds the lotus in her left hand, with her right hand in the tarjani mudra of protection. Next is Jambhala, the protector who guarantees prosperity and wealth, holding a gold sack in his left hand and a fruit in his extended right hand.[iii] A white goddess holding her left hand in the vitarka mudra of metaphysical debate and a fruit in her right hand certainly appears to be in affinity with Jambhala—possibly this goddess is his female aspect? Above this goddess in the right lateral border is another aspect of the brown goddess, perhaps a form of Tara, this time holding two lotuses and with her right hand in varada mudra.

The right lateral border shows a lineage of Buddhist masters who are both laymen and monks, though there is too little differentiation of the facial features to ascertain precise identifications. The fourth figure in the lineage has a low three-lappet hat in gold color fabric, which is worn by several different Buddhist masters in circa 13th/14th-century thangkas.[iv] As this shape hat—red or yellow in color—is sometimes worn by Taklung Tashipal, the first abbot of Taklung, and later by other monks who assumed the role of abbot, perhaps this is an abbot's hat. In this thangka, however, lacking any name inscription, the identification of the monk is not known at present.

The Tibetan Inscriptions

The four Tibetan inscriptions provide chronological clues to aid in understanding the production of this thangka and to help clarify the identity of the Buddhist hierarch portrayed here.

1. On the front, at the level of the lion and elephant throne supports, an inscription in gold paint is written below the central rug. This is in Tibetan print letters and reads:

bla ma rin po che dbon po dpal gyi thugs dam lags.[v]

"This is the high aspiration (thugs dam) of the Bla ma Rin po che (precious lama) Dbon po dpal"

Dbon po dpal (1251-1296) was a well-known Buddhist master. A scion of the family of the founder of Taklung monastery, he served as Fourth Abbot of Taklung during the years 1273-1274. After this he left Taklung Monastery to travel east to Khams, where he founded the Riwoche Monastery, of which he became the First Abbot. The implication is that Dbon po dpal personally venerated this icon.

It is unlikely that this inscription was placed on the front of the thangka by Dbon po dpal himself, insofar as he would not have referred to himself as "precious lama" since that would not reflect the customary and habitual personal humility characteristic of Tibetan monks. It is, thus, likely that this inscription was placed on the front by a later person, probably a student of Dbon po dpal who wrote this as veneration of his teacher.

2. On the reverse, at the top of the thangka, is a one-line gold inscription in Tibetan print letters in a handwriting which appears identical to the inscription on the front. It would appear that this sentence was written at the same time as the sentence in gold print letters on the front of the portrait. This inscription reads:

Rin po che Sku yal ba nas bla ma Rin po che Dbon po dpal yan chod yab sras gsum gyi rab gnas dpag du med pa bzhugs

"Here abide the immeasurable consecrations of three (generations of spiritual) fathers and sons from the precious Lama (bla ma Rin po che) Dbon po dpal upward to the precious (Rinpoche) Sku yal ba."

In terms of the three generations, this refers to the Second Abbot, Sku Yal ba (1191-1236), the Third Abbot, Sangs rgyas yar byon (1203-1272), and Dpon po dpal as Fourth Abbot of Taklung (Abbot 1272-73, lifetime 1251-1296).

Again, the inscription must be written by a disciple or student of Dbon po dpal in reverence for his teacher’s consecration of the icon and the consecrations of the two previous abbots. It clearly indicates that at the time of writing this prayer, this thangka was considered to be particularly precious due to the successively consecration by three Taklung abbots.

3. The next inscriptions consist of ten lines of script in very small Tibetan cursive handwriting, in black, in an oval shape which corresponds to the reverse of the head of the hierarch. The first portion of the inscription is Sanskrit prayers, written in Tibetan letters for five lines.

The first verse, Om Sarvavid Svaha, refers to the aspect of Vairocana known as "Sarvavid"—literally ‘the omniscient.’

This is followed by the well-known consecration prayer which starts with the words "Ye Dharma," the Dharma, a term used to refer to the teachings of Buddha, but its literal meaning is the "factors of existence.”

This is the ubiquitous and quintessential prayer of Buddhism, particularly frequent in icons of Tibetan Buddhism. The Ye Dharma verses on the causation and cessation of all phenomena may be translated thus: “Of the factors of existence (dharma) rising from a cause, the Tathagata has spoken, and of their cessation too: He the Mahashramana (the great Ascetic), who speaks truthfully (evam vadi)” ((Tibetan transcription: ye dha rma he tu pra bha ba/ he tun te sho ta tha ga to/hya ba dad te sha tsa yo ni ro da ha/ e bam ba ti ma ha sra ma na/ //))[vi]

The next five lines are a quotation from yet another Tibetan liturgical text, the Pratimoksha sutra, which is known as the Prayer of Patience or Prayer of Forbearance. These verses are included in the code of the Vinaya—the code of monastic discipline—of all monks.

The translation proposed is as follows:

The Buddha has said that patience is the best ascetic practice, and this

forbearance is the best transcendence of suffering. A Buddhist monk will

refrain from harm and injury to others, for this is not virtuous practice.

(bzod pa dka' thub dam pa bzod pa yis/mya' ngan das mchog ces Sangs rgyas gsung/ Rab tu byung ba gzhan la gnod pa dang gzhan la tshe ba dge sbyong ma yin no/)

These ten lines in black ink appear to be the original inscription at the time the thangka was produced.

It would appear that the gold inscriptions on the front and on the reverse are all later additions.

4. Immediately beneath these ten lines of verse in small cursive script in black ink is, again, a two-line inscription in Tibetan print letters in gold: "May I Kirti shri bhadra (Grags pa dpal bzang po) and the holy incomparable lama the Wisdom Guru (Shes rab bla ma) never be separated, and may I have the capacity to accomplish all the commands to purify one's own mind and guide all sentient beings (mtshungs med bla ma dams pa Prajnya Guru dang/ bdag Kirti shri bhadra 'brel med ci gsung bka' bsgrub cing/ rang sems khrul ba dag pa dang/ 'gro ba dren nus par shog)

These words were attributed to Dpon po dpal, who refers to himself by the term "I" bdag using his personal Sanskrit name (Kirtishribhadra, a literal translation of his Tibetan name Grags pa dpal bzang po), and he refers to his "Wisdom Guru," which is undoubtedly referential to the Third Abbot of Taklung, Sangs rgyas yar byon, whose Sanskrit name is Prajna Guru, ie. Shes rab bla ma. This phrase and/or identical or highly-similar sentences have been written on many thangkas and initiation cards produced for Taklung monastery; it clearly shows the personal veneration of Sangs rgyas yar byon by Dpon po dpal, who studied long years under his guidance. This inscription was written in the late 13thcentury.

Conclusions

The implication of the iconographic analysis and the totality of the inscriptions is that the present thangka was re-consecrated by Dbon po dpal in the late 13th century, and further venerated by his disciple(s) after his death.

Although written in the late 13th century, the uppermost gold inscription on the back refers to two earlier consecrations stemming from Sku yal ba and Sangs rgyas yar byon and a third consecration by Dpon po dpal. What does this imply for the identification of the present portrait? Sku yal ba’s principal teacher was Taklung Tashipal. One lifetime portrait of Tashipal has been identified: Tashipal is known to have consented to making a painting of his footprints during his lifetime, following the instructions of his teacher Phagmodrupa. The footprints are believed to be the concrete trace of the teacher’s physical body, thus “so imbued with the lama’s presence that a disciple can receive teachings from them in the teacher’s absence.“[vii] On the footprint painting, at center is a small portrait of Tashipal, seated, with his full face framed by a light goatee and his hands over his heart forming the dharmacakra mudra (see fig. 1).[viii] In the present thangka, in the center of the upper register, although the monk has his head towards Vajradhara, clearly the monk has a slight goatee and performs the dharmacakra mudra. In consideration of the consecration attributed to Sku Yal ba, the monk above his head would logically be his teacher Taklung Tashipal. It may be suggested that Sku Yal ba, following the example of his teacher Tashipal, consented to a portrait during his lifetime, to serve his disciples in the act of teaching. Although rare, there are a few lifetime portraits of distinguished monks which have been documented. Notably the portrait of Spyan snga Tshul khrims ‘bar, now conserved in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1991.152), which portrays him holding prayer beads as if to teach to his disciples.

An alternative hypothetical identification is that this portrait represents Tashipal himself, which Sku Yal ba consecrated in homage to his teacher. Although Tashipal is most frequently represented seated frontally, David Jackson has identified one portrait of Tashipal where he is represented as an enthroned seated youthful monk, 3/4 profile facing left, with similar hairline, wearing monastic robes and cloak, the hands in dharmacakra mudra, now conserved in the Alain Bordier Foundation, Tibet Museum, Gruyères (see fig. 2).

The identifications of the Taklung Abbot portraits have been re-assessed several times, due to the fact that the corpus of Taklung and Riwoche portraits now extends to several hundred known painted representations of thangkas and tsakalis. In the present context, Jane Casey has recently published the present thangka as a portrait of Sku Yal ba, the Second Abbot of Taklung, created during his lifetime. [ix]

Dr. Amy Heller, Nyon, March 8, 2018 (revised March 6, 2024)

[i] The importance of Guhyasamaja-Manjuvajra in five aspects as meditation deities, respectively in the upper register or in the lower register in the entourage, is well documented in Tibetan thangkas as of the late 12th century and persisted throughout the 13th century. The Green Tara thangka, John and Berthe Ford Collection, Walters Art Museum F.112, is dated by inscription to circa 1175, with five aspects of Guhyasamaja-Manjuvajra in the lower register.

In J. Casey's 1998 analysis of this Tara painting, these five aspects were understood to be individual female deities, while she identified the five figures of the upper register as esoteric aspects of Manjusri in the Portrait of Two Monks, Cleveland Museum of Art 1987.146, the portrait of Phagmodrupa and Taklung Tashipal. As the name implies, indeed Guyhasamaja-Manjuvajra may be understood as an esoteric aspect of Manjusri. See the essays by J. Casey-Singer in S. Kossak and J. Casey-Singer, Sacred Visions, no. 3 Green Tara and no. 26 Portrait of Two Monks (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998). Dan Martin has reviewed the analysis and chronology of the inscriptions on the Green Tara to provide the late 12th-century date (see D. Martin, Painters, Patrons and Paintings of Patrons in Early Tibetan Art, 2001: 139-190.) In two 13th-century thangka portraits of Phagmodrupa, again the five masculine aspects of Guhyasamaja -Manjuvajra are the protective deities of the upper register (Rubin Museum of Art, C.2005.16.38, and a private European collection, illustrated in S. Kossak, Painted Images of Enlightenment, fig. 54).

[ii] Several early examples of Milarepa in white robes with his hands either in the dharmacakra mudra or in his lap are illustrated in S. Kossak, 'The 'Taklung' thankas, their history and provenance reconsidered,” in Painted Images of Enlightenment, figs. 114-119, 121. The iconography of Milarepa holding his hand to his ear in the pose of an Indian singer only became current after the circulation of his biographies as of the mid 15th century ( see Treasury of Lives, https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Milarepa/3178).

[iii] Among the earliest sculptures of Jambhala are circa 9th-century Indonesian models where the nakulaka bag is held (see fig. 71, S. and J. Huntington, Leaves of the Bodhi Tree, Dayton Art Institute, 1990), as in the present thangka, while later, particularly in Tibet, Jambhala is represented holding a mongoose spewing jewels rather than a bag shaped like a mongoose. The mongoose is the natural enemy of serpents, thus, according to Indian tradition, the mongoose is said to have taken the gems from the naga serpents who are the guardians of the treasures of the subterranean world beneath the earth.

[iv] David Jackson, for example, has studied the portrait of Taklung Tashipal, early to mid-14th century, collection of Mimi Lipton, illustrated as fig. 4.12, and Phagmodrupa with his Previous Lives, circa 14th century, Rubin Museum of Art, F1998.17.4 (HAR 666) illustrated as fig. 5.9, p. 143, in D. Jackson, Mirror of the Buddha, New York, 2011.

[v] This inscription is not unique to this portrait, but also is written, in the same position on the lower edge of the throne, on two other thangkas associated with Taklung or Riwoche monasteries. One is a portrait of an abbot (see figure 2), now conserved in the Alain Bordier Foundation (AB 36, 27.5 x 20.7 cm.). This portrait was first identified by David Jackson as Taklung Tashipal, the founder of Taklung, and attributed to late 13thcentury (fig. 2.15, p. 34, The Nepalese Legacy in Tibetan Painting, New York, 2010) and later identified by Gilles Béguin as Dbon po dpal and attributed to the late 13th century (fig. 29, pp. 90-91, Art Sacré du Tibet Collection Alain Bordier, 2013). Neither of these scholars discussed the inscription on the front, although Béguin illustrated the reverse of the thangka with numerous inscriptions (which are not identical to those on the present thangka). The second thangka on which this gold inscription figures on the lower portion of the throne is a Vajravarahi mandala, private collection, first published by Jane Casey Singer as fig. 40 in "Taklung Painting" (Tibetan Art, London, 1997) and restudied as fig. 20 in Sacred Visions (New York, 1998). Casey attributed this painting to 1200-1210, stating that the inscriptions were later additions. On the Vajravarahi mandala, the inscriptions—both on front and reverse—are virtually identical to the present thangka. The translation provided by Casey has been subject to rigorous philological study by Dan Martin (Hebrew University, Jerusalem). Dan Martin reviewed all these inscriptions and their historic context, Paintings, Patrons, and Paintings of Patrons in early Tibetan Art, 2001: 139-190 (see pp. 160-164 on these inscriptions).

[vi] See this writer's essay "The Tibetan Inscriptions: Dedications, History, and Prayers," in P. Pal, Himalayas: an Aesthetic Adventure, Art Institute of Chicago exhibition catalogue, 2003: 286-297.

[vii] Kathryn Selig Brown, Eternal Presence, Handprints and Footprints in Buddhist Art, Katonah Museum of Art exhibition catalogue, 2004: 23-24.

[viii] Footprint thangka of Taklung Tashipal, Musée National des arts asiatiques-Guimet, MA 5176. Donation Lionel Fournier, 1989.

[ix] Jane Casey, with Gyurme Dorje and Liao Yang, Taklung Painting: A Study in Chronology, Serindia Publications, 2 volumes. 2023: vol. 1: 233-235, catalogue 15.

fig. 1 ~ Footprint thangka of Taklung Tashipal (detail), Musée Guimet, MA 5176

fig. 2 ~ Taklung Abbot portrait identified as Taklung Tashipal with his lineage, manifestations, and two successors, according to D. Jackson, Nepalese Legacy in Tibetan Art, 2011, fig. 2.15), Alain Bordier Foundation (AB 28), late 13thcentury, 27.5 x 20.7 cm.; ( see also reproduction in G. Béguin, Art Sacré du Tibet, 2013, pl. 29)