Provenance:

Collection Juelemann

Joachim Baader, Munich, acquired from above in the late 1990s

German Private Collection

This painting presents a ravishing vision of Manjushri, the embodiment of Buddhist wisdom. Against a background of azurite blue, layered with blue, green, and red clouds, the saffron-complexioned bodhisattva engages the viewer with his focused gaze and draws us into his world. Holding aloft a flame-tipped sword and the stem of a lotus flower supporting the Perfection of Wisdom (Prajnaparamita) manuscript, he is crowned, bejeweled, and enthroned. Manjushri’s celestial entourage include two Buddhas, flanking him in the upper portion of the painting, two bodhisattvas (Vajrapani and Avalokitesvara) in the middle ground, and Manjushri and Saraswati aside the lower throne. Below are the deities Hayagriva, Vajravidarana, Bhurkumkuta, Panjara Mahakala, and Shri Devi.[1] Cloud-borne apsaras pour libations from above.

fig. 1

This vision is made palpable by the artist, whose mastery of painterly techniques convinces us we are in a real world. The palette is extraordinarily vibrant and rich, innervating the eye. Depth is established by overlapping forms and by the juxtaposition of contrasting colors. The two-dimensional surface of the painting is also expanded by long clouds just above the central deity’s halo, which trail into the background, coaxing the eye into perceiving depth. Foliate scrolling is ingeniously interpreted, typically drawn in a darker line, often against a deeper hue, as seen in the azurite blue halo of Manjushri and his malachite-green throne-back cushion. (fig. 1)

fig. 2

The manner in which the textiles drape the wearer is another aesthetic highlight of the painting. Informed by careful observation of the natural fall of fine silks, Manjushri’s shawl rests convincingly across the shoulders, flowing along the torso and into the lap. Heavy shading suggests the weight of fabric as it cascades from the upper right arm. The folded legs are covered in layers of fine silks, the malachite-green fabric creased at the knees and partially covered with a gold-embossed coral-red silk, bordered in a deep blue silk with gold floral scrolls. The drape and fall of these delicate cloths also enhance the depth and vivacity of the painting. The convincing depiction of gem-encrusted gold jewelry on Manjushri’s torso, falling off the left shoulder to the lap and disappearing behind the right shoulder, is likewise informed by close observation of the natural fall of a long chain of gold jewelry. The figures possess presence, as with Saraswati, who appears to be listening to the music she plays on her stringed instrument. (fig. 2)

The painting style evident in this work is closely related to the style seen in murals of the Gyantse Kumbum, built between 1427 and circa 1440. Located along the lucrative trade route between Lhasa to the north and the Kathmandu Valley to the south, the Kumbum and related buildings were created during a thirty-year period of peace and prosperity, in which the rulers of Gyantse expressed their confidence and economic prosperity by constructing ambitious religious monuments.[2] As Dr. Heather Stoddard has observed, the Kumbum was “a major technical, economic and religious endeavour, and remains one of the finest surviving architectural and artistic monuments in Tibet today.”[3]

The Kumbum’s discerning patrons conceived of an octagonal stupa, a three-dimensional mandala, with 75 interior chapels on nine stories, rising to 35 meters.[4] The monument was meant to encapsulate the entire Buddhist teachings of the day and to provide a visual map to enlightenment. Its interior represents “the deities of all the chief tantric cycles and the spiritual lineages who propagated them, [and] affords a global view of the world as conceived in the Indo-Tibetan Buddhist culture of the 15th century, a visual summa of all the knowledge of the time.”[5] Pilgrims moved from chapel to chapel, beginning on the lowest floor, encountering deities in their celestial realms, ascending to the ultra-refined, most subtle teachings on the upper levels.

Recorded on the walls are also the names of those whose donations built the monument, including the names of approximately 150 families and individuals, the inscriptions often specifying the nature of their donations. Rabten Kunzang Phakpa (rab brtan kun bzang ‘phags pa, 1389-1442), ruler of Gyantse at this time, laid the foundation of the Kumbum when he was 37 years old.[6] His brother, Rabjor Zangpo, and his mother, Changsem Dagmo Palchen Gyalmo (byang sems bdag mo dpal chen rgyal mo), are also mentioned in the Kumbum inscriptions as patrons of various chapels, as are many others from the Gyantse region and elsewhere in Central Tibet, including the head of the army (dmag dpon chen mo) and the Prime Minister (blon chen).[7] Rabten Kunzang Phakpa commissioned artists from all over the region to create the murals and sculptures within the monument. Artists’ names (sometimes a master and his atelier) are recorded in the chapels where they did their work. The names of about 34 painters and 13 sculptors are recorded in inscriptions in the Kumbum chapels, as well as the region of their residence.[8] Most were Tibetans from the Central Tibetan regions of Lhatse, Sakya, Jonang, Nenying, Shalu, Drongtse, and Gyantse.[9]

The stated purpose for creating these paintings and sculptures was the aspiration that all sentient beings experience the great awakening of Buddha.[10] In the dome of the Kumbum is an inscription that may be translated: “May all those who gave life and materials for the building of this great Stupa [mchod rten] and all those who had taken at least a step for this goal quickly obtain [enlightenment]. May all those who see this Stupa, hear it spoken of, remember it and have faith and joy from it, reach supreme illumination.”[11]

fig. 3

Specific comparisons between this painting and details in the murals of the Gyantse Kumbum can be cited. The same luxurious textiles, highlighted with delicate gold designs, and likely inspired by Chinese silk textiles of the period, are ubiquitous in the Gyantse murals, as well as the manner of their drape.[12] The physiognomy and expression of the central figure find many parallels in the Kumbum murals.[13] The blue and red gem-inset gold flaming double halo of the central figure features throughout the Gyantse Kumbum murals.[14] Fingers touching in a gesture with prominent short white nails can be cited.[15] Manjushri’s seat consists of a two-tiered throne with curved wooden legs and adorned with gold floral design and gold attachments, the interstices between the two levels supported by two lions and two Ganas who uphold the upper tier with their hands. Similar work can be found in the Gyantse murals.[16] The three large flowers that appear above Manjushri’s halo are seen also in the Kumbum murals.[17] The upper lotus petals of Manjushri’s seat appear in a mural of Avalokiteshvara in a third floor chapel.[18] The unusual, long white stylized clouds can also be found in the murals of Kumbum.[19] The particular shape of the bulbous cranial protuberance (ushnisha) of the Buddhas is likewise found in the murals of the Kumbum.[20] (fig. 3) Manjushri’s necklace, with delicate gold settings of coral and lapis, is much like that in a mural depicting a saffron-colored Maitreya Buddha.[21]

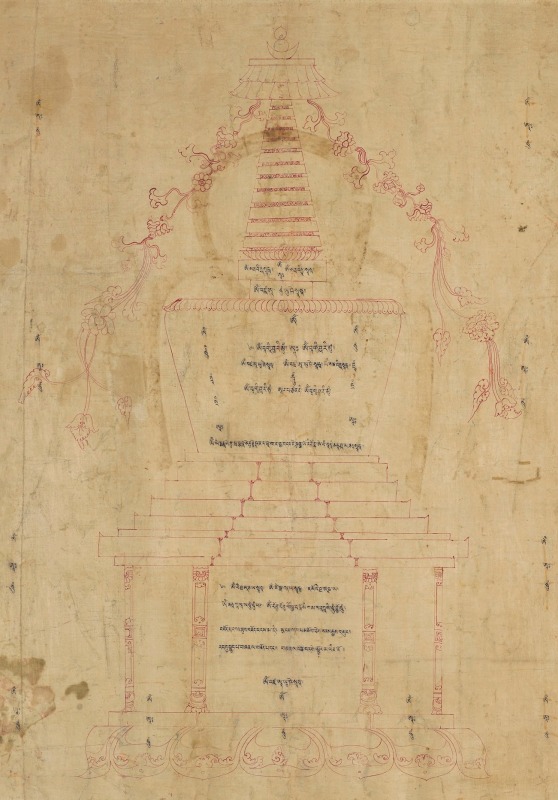

fig. 4

The painting verso is rendered with as much aesthetic sensitivity as the obverse. (fig. 4) A Buddhist reliquary stupa is drawn in a delicate ruby-red line. Floral tendrils attached to the stupa parasols fall on either side of the reliquary’s dome chamber. The dome is supported by a lotus and multi-tiered platforms.[22] Black Tibetan calligraphic script records mantras and prayers within the interior of the stupa drawing. The inscriptions include consecration mantras (ōṃ sa rva vidyā svā hā), vivifying mantras for particular deities, and two verses drawn from Buddhist literature. The first is the ye dharmā verse, which contains the essence of the Buddhist teaching, written in Tibetan. This transliteration of a Sanskrit verse is sometimes referred to as the verse of Dependent Origination: ye dha rmā he du pra bha vā he dunte ṣān ta thā ga ta hya va dat te ṣāñ ca yo ni ro dha e vaṃ vā tī ma hā śra ma ṇaḥ svā hā// It may be translated: “Those things which arise from a cause, the Tathagata has declared their cause. Their cessation too the great renunciant (Śramaṇa) has stated.” The second verse, sometimes referred to as the Patience creed, is composed in Tibetan language. The patience verse is likewise a distillation of Buddhist teachings, in this case derived from the Pratimokṣa Sūtra: bzod pa bka’ thub bzod pa dam pa ni // mya ngan ’das pa mchog ces sangs rgyas gsung// rab tu byung ba gzhan la gnod pa dang// gzhan la ’tshe ba dge sbyong ma yin no// It may be translated: “The holy ascetic practice of patience is the best path to Buddhahood, thus the Buddha has said. For a monk to harm others is not virtuous practice.”

The many close similarities between this painting and the murals of the Gyantse Kumbum suggest the artist may have been active in the creation of the Gyantse murals. Other contemporaneous paintings on cloth can be cited as exhibiting the color palette and other elements of the Gyantse Kumbum style, though they are far less closely associated than this remarkable painting of Manjushri.[23]

Jane Casey

[1] See Himalayan Art Resources for brief online descriptions of these deities, https://www.himalayanart.org

[2] Erberto Lo Bue and Franco Ricca, Gyantse Revisited (Firenze: Casa Editrice Le Lettere, 1990), p. 66

[3] Heather Stoddard in Thomas Laird, Murals of Tibet (Cologne: Taschen, 2018), p. 297

[4] Stoddard in Laird, Murals of Tibet, p. 292. Henss notes the monument’s total height as 42.5 m., Michael Henss, Monuments of Tibet, 2 vols. (Munich: Prestel Publishing, 2014), caption to figure 766, p. 533

[5] Franco Ricca and Erberto Lo Bue, The Great Stupa of Gyantse (London: Serindia Publications, 1993), p. 32

[6] Ricca and Lo Bue, The Great Stupa of Gyantse, p. 27; Stoddard in Laird, Murals of Tibet, p. 296

[7] Lo Bue and Ricca, Gyantse Revisited, pp. 245-52

[8] Giuseppe Tucci, Gyantse and its Monasteries, Part 1 (Rome: Reale Accademia d’Italia, 1941, reprint Delhi, 1989), pp. 19-20; Giuseppe Tucci, Gyantse and its Monasteries Part 2, pp. 137-273; Stoddard in Laird, Murals of Tibet, p. 297; Henss notes the names of 36 painters and 13 sculptors, Monuments of Tibet, p. 546

[9] Henss, Monuments of Tibet, p. 546

[10] Tucci, Gyantse and its Monasteries Part 2, p. 158

[11] Tucci, Gyantse and its Monasteries Part 2, p. 24; slightly adapted from Tucci’s translation

[12] Ricca and Lo Bue, The Great Stupa of Gyantse, pp. 133, 141-52, and passim; Laird, Murals of Tibet, p. 342 and passim

[13] Laird, Murals of Tibet, pp. 301, 324, 340, 346

[14] Ricca and Lo Bue, The Great Stupa of Gyantse, pp. 150-51, and passim

[15] Laird, Murals of Tibet, pp. 335, 345, and passim

[16] See Henss, Monuments of Tibet, fig. 788 for a very similarly-designed throne base beneath a polychromed clay sculpture, with a wooden base similar in design to Ming prototypes, in Gyantse’s Tsuglagkhang, dated c. 1420

[17] Lo Bue and Ricca, Gyantse Revisited, pls. 107, 147-54, and passim

[18] Ricca and LoBue, The Great Stupa of Gyantse, p. 131

[19] Laird, Murals of Tibet, p. 337

[20] Laird, Murals of Tibet, pp. 338-39; Henss, Monuments of Tibet, fig. 770, p. 537

[21] Henss, Monuments of Tibet, fig. 771

[22] The dome and parasols of the stupa on the painting verso are very like stupas in the murals at the Kumbum. See Lo Bue and Ricca, Gyantse Revisited, pp. 249-50; Ricca and Lo Bue, The Great Stupa of Gyantse, p. 287

[23] See Steven Kossak and Jane Casey Singer, Sacred Visions (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 180-87; Jane Casey, Naman Ahuja, David Weldon, Divine Presence (Barcelona: Casa Asia, 2003), pp. 152-55; David Jackson, Mirror of the Buddha (New York: The Rubin Museum of Art, 2011), fig. 2.35

Further reading:

Michael Henss, The Cultural Monuments of Tibet, 2 vols. (Munich, London, New York: Prestel, 2014)

Thomas Laird, Murals of Tibet (Cologne: Taschen, 2018)

Erberto Lo Bue and Franco Ricca, Gyantse Revisited (Torino: Casa Editrice Le Lettere, 1990)

Franco Ricca and Erberto Lo Bue, The Great Stupa of Gyantse (London: Serindia Publications, 1993).

Giuseppe Tucci, Gyantse and Its Monasteries 2 parts, Indo-Tibetica IV.1 and IV.2 (Rome: Reale Accademia d’Italia, 1941); English translation and reprint, New Delhi, 1989

Giuseppe Tucci, Tibetan Painted Scrolls, 2 vols. (Rome: libreria dello Stato, 1949); reprint, SDI Books, 1999